The international seabed is the ‘common heritage of mankind’ (or humankind). In principle then, it your heritage, and mine. It is a place, as global citizens, we have rights to (and towards). But is it somewhere we can actually access (to in turn access those rights?)? How can we enact our rights to the seabed?

This blog post reflects on one avenue we (myself, Prof Kimberley Peters, and Dr Katherine Sammler) have been pursuing to answer this question. It started with a small thought, a provocation on our local, personal relationships to global scales, and then global environmental concerns (such as the protection of the seabed as an extractive frontier).

We therefore have set out to follow pathways of access to ‘The Area’ (the name given the international seabed). One pathway we started to trace was whether the seemingly distant seabed was closer than we thought. Could we perhaps encounter it on land? Indeed, and this may surprise readers, there are many ancient seabeds that are now walkable.

Ancient seabed materials are everywhere. My little Japanese hibachi barbecue was made from compressed diatomaceous earth, that is, ancient fossilized diatoms that accumulated on the seafloor and became a soft sedimentary rock. During my PhD research I visited an Ediacaran archaeological site where the fossilized bodies of the first known multicellular life were being uncovered on beautiful plates of stones, nestled amongst the preserved gentle ripples in what was once the sandy seafloor of a shallow inland sea. Kim pointed to the Jurassic Coast near Dorset as another well-known example of ancient seabed sites. Many of the sandstones and marbles that our grandest buildings are constructed of were originally sedimentary seabed materials.

But were these really examples of ‘The Area’ on land, we asked ourselves. Of course, very technically, the current legal regimes that define the international seabed did not exist in ‘ancient’ times. Places that are now solid, grounded, landed, were once sea and would have been part of such regulatory schemes, had they existed. The example therefore raised interesting questions about how the ‘The Area’ is constructed by how we define it. Physically. Temporally. Legally. And so on. But there was another intriguing question for us. Why were so many of the terrestrial sites we were looking at formed from ancient shallow seas?

The answer, it turns out, is fairly straightforward. Oceanic plates are denser than continental plates, so when they collide the oceanic plate is usually subducted or sinks below the continental plate into the earth’s mantle to be recycled. But as we found out there are exceptions: ophiolites are geological anomalies where sections of oceanic crust and upper mantle have been uplifted for various reasons and lie exposed above continental plates.

This part of our project, focused on accessibility of The Area, sought to take both the ‘heritage’ and ‘access’ parts of our enquiries seriously by conducting a visit to an ophiolite to examine its accessibility. A key factor in choosing a site to visit was how easy, fast, and cost effective it was to get to this ancient part of our common heritage. There are several European ophiolites that we determined as among the most accessible options, both financially and in terms of ease of travel, and we decided to select just one. These included the Chenaillet ophiolite in the Franco-Italian Alps, the Aiguilles Rouges ophiolite in Switzerland, the Ballantrae complex on mainland Scotland and the Island of Unst in the Scottish Shetland Islands, the Tauern Window in the Austrian Alps, and the Troodos ophiolite in Cyprus.

After working out the costs and travel times for each of these ophiolite options we eliminated the Scottish and Cypriot options because of their remoteness from us in Oldenburg (see image of the google maps transport route from Oldenburg to Ballantrae), despite their having the clearest information available online.

Left with the three Alps options, we began by emailing the organisations that appeared to be most closely related to the ophiolite to request advice on the best way to visit. The Tauern Window national park was the only entity that responded, and they gave us suggestions for walking routes within the national park that we could take to encounter their ophiolite geology. An interesting point was that their national park has several geotrails specifically designed for the public to learn more about the alpine geology but none of them included ophiolite information. Realising that if we were to hike a path with no geological expert we would be unlikely to understand what we were looking at, the park offered us their rent-a-ranger service. After several months of back-and-forth emails, relying heavily on DeepL’s translations and Kristin Tietje’s generous proofreading, the national park also coordinated for an English interpreter to join us for the day.

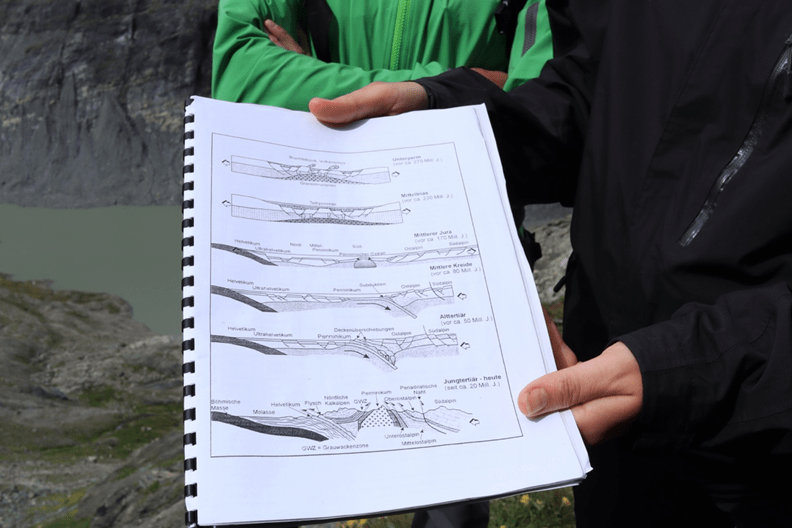

This is how Dr Katherine Sammler and I ended up balanced on the side of a mountain studying geological diagrams with our ranger and interpreter, while Kim was stuck at home with a broken leg.

Kate and I were perched on the moraine ridge of a rapidly receding glacier. We had a majestic, cloudy view across the glacial valley to the Großglockner, Austria’s highest mountain. Our national park ranger and interpreter were carefully explaining the geological history of the Tauernfenster or Tauern Window, the specific geological structure of the area that included layers of oceanic crust. We tried our absolute best to listen and understand, but as Anna our interpreter pointed out, it’s difficult even for geologists to really comprehend and explain the geological history of the Tauern Window.

Photos: Amelia Hine.

The ocean crust layers were especially visible in the glacial area we were visiting and as we slowly hiked down to the valley below, we were introduced to the variety of green rocks that signified they were originally ocean crust. In particular we became familiar with serpentinite, gabbro, greenschist, and peridotite (see the below images).

These rocks had once been part of the ancient Penninic ocean crust. This ocean crust had originally been subducted as the African continental plate moved toward the Eurasian plate. During this period some of the original crust minerals were transformed through pressure and heat, producing the serpentinite and greenschist. Due to a subsequent process of uplift and the sideways movement of the overlying strata alongside erosion, however, these crust minerals were pushed upwards to the surface in the area of the Tauern Window, where we are able to encounter them. So here we were, up high, but also on an ancient seabed. The geophysical history of these crust minerals had an impact on our ability to engage with and understand them as ocean crust. They did not resemble anything clearly ocean-bottom-esque. Certainly, without our guides we would not have had a clue what to look for or how to interpret it. But then, what does the deep international seabed really look like? Why should a crust look anything like a seafloor surface? And are there actually places that might give us a sense that we are looking at or walking on the seabed?

Photos: Amelia Hine.

When we first began contemplating terrestrial seabed locations to visit, we had thought to also consider Iceland as a place that might be future seabed, since it sits directly on the northern mid-Atlantic ridge where new oceanic crust is continually produced. I had a phone conversation with an AWI geophysicist to understand whether Iceland would actually become seafloor at some point. Although she reassured me that it wouldn’t, she did encourage our thinking in a different direction by pointing out that Iceland is effectively the same as the seafloor albeit above the sea.

The volcanic behaviours are the same as you would see in rift zones on the seafloor, with the clear distinction that the lava behaves differently because it’s erupting into air rather than water. On the seafloor pillow lava is formed, which is texturally and aesthetically different to lava formations on land. From a zoomed out landscape perspective Iceland could be considered very similar to the seafloor, but on a more micro level it isn’t entirely comparable with factors such as erosion, weathering, and vegetation making it visually distinct.

In a similar vein, the globally recognised best example of an ophiolite is the Samail ophiolite located in Oman. It is the largest and apparently best-exposed ophiolite globally, and ostensibly the most studied due to these factors. Having sat through a number of the University of Derby’s charmingly dated videos from a geological field excursion to the Oman ophiolite, I don’t think that the Samail ophiolite offers a radically different experience for the nongeologist to that of the Tauern Window. The possible exception is the section of pillow lava, which would have emerged directly at the intersection of seafloor and water column, and which it is easier to imagine as a seabed because of its formation at the surface.

Indeed, the difference between an ophiolite and the seafloor-esque landscape of Iceland is that the former is effectively a cross section of the ocean floor, whereas Iceland is a rough simulacra of the seafloor surface. Perhaps a cross section, no matter how well preserved, can never give a full sense of encounter with The Area?