Only within the last couple decades have social science and humanities scholars intentionally taken their disciplines offshore and into the depths of the sea. Academic and policy circles now recognize the justification for interdisciplinary ocean research. Such efforts have brought attention to the ocean’s importance to every aspect of our lives.

This turn has not discovered our relations with the oceans anew, but has given voice to, and legitimized connections that ocean-minded peoples have long known, but which have been largely ignored by policy makers and institutions. Moving forward, researchers are calling for projects that engage in “critical ocean studies” that are more inclusive in their perspectives and can offer better frameworks and practices for living under the Anthropocene. This is the project of marine political ecology. It is a perspective of joining critical politics with environmental study to transcend typical boundaries in light of our changing planet.

“I am the ocean and the ocean is me.”

Māori axiom

Indeed, within this “oceanic turn,” the ocean itself exceeds individual disciplines or narrow categorizations. Yet, as scholars we often engage it piecemeal, discussing the ocean as the element of water or its waves, other times as fish, petroleum, mineral, or sand resources, and increasingly as data, archive, or media. Outside of academic discussions, ocean management practices commonly disassemble ocean spaces and ecosystems into disparate parts by sector or jurisdiction. The preamble to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the proclaimed constitution of the oceans, declares “the problems of ocean space are closely interrelated and need to be considered as a whole”. Yet, this statement is followed by two hundred pages dedicated to dividing up the world’s oceans into fragments based on boundaries, species, uses, users, depths, and mobilities. It finishes without ever putting the pieces back together again, towards recognizing its connections and relations.

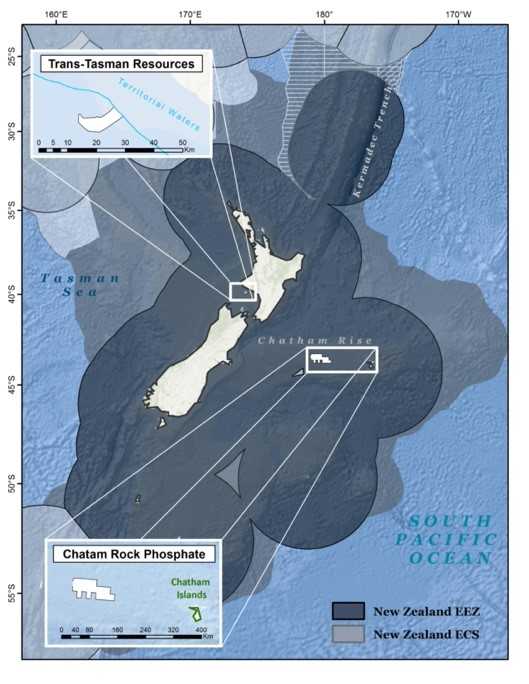

For example, in Aotearoa New Zealand, Parliament passed the 2004 Foreshore and Seabed Act, employing UNCLOS jurisdictions to nationalize the seabed, ignoring traditional ocean tenure of Indigenous Māori Tribes. The ongoing struggle involves questions not only over the ‘ocean grab’ by a settler nation-state, but more fundamentally whether it is productive to divide ecosystems and management practices between land and sea, as they typically are in Western frameworks. Māori have long held a viewpoint which situates human and nature within a framework of kinship, extending from mountains to sea. As two seabed mining companies seek to extract minerals off their coasts, these differing worldviews have real impacts both on and offshore.

So, a broad change in thinking about ocean care is arguably necessary: one that is not based in command and control of nature, but existing with, in, and for our living environment. We need to not only develop a framework that extends beyond disciplinary divides, but one that expands worldviews regarding our fundamental relationship to nature. Proposed shifts in thinking have included closing the human-nature divide via embracing the physical world through concepts of entanglements, living relations, kin, and natureculture. Other have suggested we must learn from and think with the ocean as part of our society and part of us. The Māori axiom, “I am the ocean and the ocean is me,” was used in testimonies against the Trans Tasman Ltd. seabed mining project, drawing attention to the inseparability of those living within this coastal environment. In fact, several Tribes have recently been successful in securing rights of personhood for a river, a mountain, and a fern forest. The complex outcomes from these designations are still unfolding, but will have important lessons for new ways of thinking about our relations with nature.

Recent policy-focused literature provides evidence of a shift towards more holistic socio-ecological framing allowing for integration of information across disciplines, jurisdictions, and scales. And while it may be impossible to think and practice ocean care without some categorizing and simplifying of its complex whole, we may choose more just and equitable divisions with which to engage. Most importantly, we must always recognize that these divisions while they may be entrenched, are not constants of nature, and must be adapted or discarded as necessary. This is what a marine political ecology perspective can offer.