Gabriel Gadsden joined the Marine Governance Group at HIFMB for ten weeks as part of Global Sustainability Scholar GSS Fellowship to understand the work of university researchers in the social sciences, and in the study of oceanic management for biodiversity.

As an honorary member of the Marine Governance Group, he was tasked to research nature’s contributions to people derived from the Wadden Sea and the synergies between known biodiversity change to aid in future governance decision making. Here is what Gabriel found:

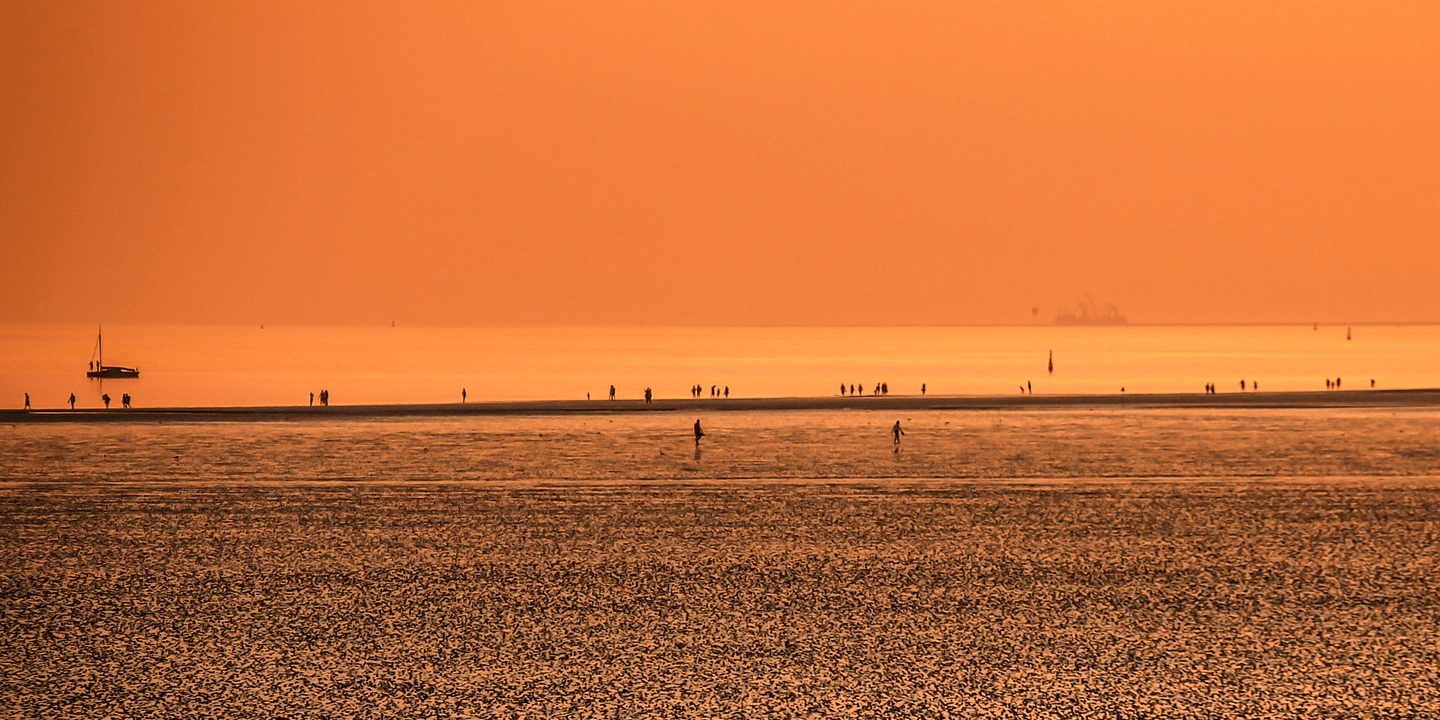

The Wadden Sea. Or not? Depending on when you visit you may be hard pressed to classify it as a sea at all. Jokes aside, the Wadden Sea is and should be revered for its biodiversity and cultural heritage. For thousands of years this body of water situated between the Frisian islands and mainland of The Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark has been shaped by the elements, and a lifeline for wildlife and humans alike. The intense tidal patterns which drive coastal sea level from less than .5 meters to over 4 meters creates the largest unbroken tidal flat system in the world. This allows marine organisms of all shapes and sizes to flourish and draws in other migratory species like birds and seals from great distances. Humans in turn have benefited from this abundance but they have also been aided by the surrounding marsh lands as barriers to harsh winds and coastal flooding.

However, as with most things, climate change and other anthropogenic forces have disrupted the balance of the Wadden Sea. Sea level rise and more frequent and intense storms have caused an incessant battle of dike building to hold back water while increasing water temperatures and changes in water chemistry put the already vulnerable population of species at risk of collapse. In a place that relies heavily on the sea for subsistence and tourism the need for successful adaptation and management is paramount to the continued success and grandeur of the Wadden Sea. To make matters more complicated, the Wadden Sea was given the title of a UNESCO world heritage site in 2009. Though this title did little in the way of changing the matrix of policy governing the Wadden Sea it did heighten attention towards the precarious and ever evolving seascape.

In the following decade, climate change has continued to put pressure on the Wadden Sea and the inhabitants – human and more-than-human – who call it home. And while there have certainly been efforts by unilateral and tri-lateral governance the effectiveness of these measures is still up for debate. Part of the issue could be the very way governance is conducted. Often, governments interact with only a few ‘key’ stakeholders and utilize scientific findings in ways that could remove greater nuance from results, should more stakeholders and perspectives be included. Though efficient, this approach can lead to a discrepancy in enforcement and unintended consequences for other stakeholders and organisms. To overcome some of the past shortcomings, a group of researchers at HIFMB set out on a multi-level plan to bring together both social and natural science techniques to ensure future policy reflects both accurate quantifiable data and voices of different stakeholder groups through the MARISCO project (as well as other related research).

Stakeholders

To begin to move towards that goal, one step is understanding who the stakeholders of the Wadden Sea are and if they are documented in the academic literature. Using a systematic review, we investigated journal articles of the last two decades that explicitly involved stakeholder engagement with the Wadden Sea. Not surprisingly, much of the research to date has been geared toward policy creation, implementation, and assessment. The review also found that coastal water management, fisheries, and tourism were most often addressed, perhaps at the exclusion of other stakeholders such as the military. Indeed, there are many stakeholders that utilize the Wadden Sea for various resources that are either given scant attention or left out completely. Energy, medicine, agriculture and recreation are notably lacking from the body of literature as it relates to stakeholders and the sea. Moreover, only 20% of papers utilized stakeholders from more than one country, although the Wadden Sea Forum utilizes multiple tri-lateral collectivism in decision making. As such, ‘joined-up’ understanding, that crosses boundaries, is somewhat lacking. While in step with stakeholder engagement of other marine sites, the Wadden Sea stakeholder engagement leaves much to be desired for a UNESCO site. Ultimately, we hope this review brings a heightened sense of awareness of the complexity of stakeholders in the region and spurs greater enthusiasm from both academics and policy makers to bring more voices to the table when crafting policy surrounding the Wadden Sea.